The end of the school year is getting closer and we (teachers and students alike) are all a little weary. At this time of year, I notice that the inquiries in many classrooms start to peter out and practice sometimes reverts to worksheets and themes. This change is problematic for several reasons:

- There is still so much going on in children’s play, regardless of the season. When we stop paying attention, we miss lots of valuable learning.

- The summer regression (sometimes called the summer learning loss) is a real thing, particularly for students who don’t have a lot of literacy support at home. We need to make the most of the time that we have with students; we can’t afford to lose any precious minutes to classroom activities that aren’t moving learning forward (like watching movies or completing word searches).

- For some students, holidays aren’t a happy, carefree time. When we shift our instructional focus towards themes related to summer holidays, we put a lot of stress on those students who may not be looking forward to 8 weeks spent at home. We impose our own anticipation of summer onto them and create needless anxiety.

When I’m teaching ballet, I’ll sometimes stand on a chair or sit on the floor to, quite literally, see my class from a different angle. I’ve taught some of my students for a decade or more and I need to find ways to see them with new eyes so that I can continue to challenge them and help them progress.

The same thing can happen in our classroom practice and, while standing on a chair may not be the best suggestion (or so my health and safety manual tells me), we do need to find ways of seeing our students with fresh eyes, especially as we near the end of our time together.

In the last couple of days, I’ve thought about two ways we might shift our perspective.

Earlier this week, I accompanied a group of students on a community walk through their small town. We noticed lots of interesting changes in the environment: daffodils blooming, trees budding, and bugs… so many bugs! The kids were simultaneously fascinated and terrified by an old house that they were convinced was haunted.

Among the things they collected on our walk were pine cones from the large, mature red pine trees that lined the streets. When we got back to the classroom and looked more closely at them, the kids noticed that the shape of the pinecone resembled the shape of the shells we had observed and drawn on one of my previous visits. This gave us an opportunity to revisit the drawings we had done before and to remember the strategies we had used to capture the shape of the shells. Revisiting work you’ve done during the year and looking at it with fresh eyes can leapfrog into something new and interesting. You may want to enlist colleagues to work through a documentation protocol with you to help you see your experiences from a new perspective.

Another strategy that can spark fresh engagement and activity is sharing the work of one child whose work has caught your attention.

A couple of weeks ago, I was visiting a class and noticed one boy walking the same trajectory over and over again.

He was talking to himself as he walked and clearly had a purpose to his pathway.

When I asked him what he was doing, he replied that he was walking on his secret path and he showed me where his path went.

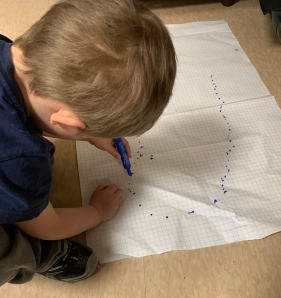

I wondered how he might be able to share his path with his classmates and he decided that he needed to draw a map.

At first the map was just a series of dots in a curved line but as we talked, he realized that he needed to represent the starting and ending points of his pathway: “I start at the water bottles and I end at the library.”

This map drawing attracted other students who then began drawing their own maps which led us on a journey through the school following their maps up and down stairs and, eventually, to the library.

When we returned, we shared the original map with the whole class which has since led to more map making. What began as a single child walking through the class, became a much larger project that may see this class through to the end of the year. If we hadn’t pulled on that thread we wouldn’t have been able to weave that pattern together. Where are the threads in your classroom? How can you weave them together to create the tapestry that will wrap up your year?