There are conversations in all of our lives that we have repeatedly.

“Did you brush your teeth? Are you sure?”

“Do you have to pee? Please try to go before you put your snow pants on.”

“Where is/are your lunch box/agenda/library book/snow pants/mitts?!? The bus is coming!”

Clearly, I’m ready for winter to be over, already.

Beyond those quotidian rants however, there are professional conversations that I’ve had so many time they’re staring to feel scripted.

One of those well-rehearsed conversations is about the Arts and whether or not students should be encouraged or even allowed to pursue them past high school. Sometimes the conversation is even about high school courses and whether students “have time” for subjects like Music and Visual Arts in their timetables.

In Ontario, students are required to complete one Arts (music, drama, dance, visual arts, media arts) credit during their four years of high school. One. For some students, that’s all they do because that’s all they want to do… and that’s fine. I understand that for those students, the Arts are not going to be where they find their passion and I can accept that. I still think that in the interest of human wellness we should be requiring more than one secondary Arts credit but this particular post is about another kind of student: the kind that wants to pursue more Arts credits but feels that they can’t.

The students I’m thinking of are talented in many areas, academically capable, high achievers. They excel at school and beyond. Their horizons are wide open and their futures are bright.

Unfortunately, what tends to happen as these students progress through high school and begin to make choices that will shape their career pathways, is that we, the well-intentioned adults in their lives, discourage them from pursuing pathways that we feel are less likely to safeguard their financial futures. We steer them towards maths and sciences because we think that’s where the jobs are.

We’re not altogether wrong. There absolutely are job vacancies in those sectors: Statistics Canada reports 28,095 vacancies in professional, scientific and technical sectors in the third quarter of 2017. However, our well-meaning advice is having unintended consequences.

In many Ontario secondary schools, teachers refer to the “six-pack” of grade 12 courses that many motivated, university-bound students take in their last year of high school: Chemistry, Biology, Physics (the Sciences), Advanced Functions, Calculus and Vectors, and Mathematics of Data Management (the Maths). That’s a lot of very intense courses to take during one year, and a lot of pressure to be ready for those courses by taking the pre-requisites in grades 9, 10, and 11. Students also have a mandatory grade 12 English credit to complete. It sure doesn’t leave a lot of time to be in the band.

The conversation therefore becomes about whether these students have time to “waste” on subjects like music and dance, given that they’ll “never get a job doing that.”

People have actually said that to my face: “Oh, my son/daughter/student will never get a job doing that (Art, Drama, Dance, Music) so why would they pursue it?” Keep in mind that I have two degrees in Dance and that I have several jobs that use my Arts training every day. There’s a lot to unpack here.

First, there’s the assumption that the only purpose of education is to prepare you for a job. What kind of impact is that having on our kids? Is their only value as income-earners, cogs in an economic wheel? What about their value as humans, as thinking, feeling, creative beings? We wonder why people become less creative as they age while we simultaneously pressure them to abandon the activities that honour and foster their creativity – the activities that make them happy. It shouldn’t surprise us when they fail to develop the skills that we repeatedly tell them don’t matter.

Second, people who make this argument assume that students have to make a choice between pursuing the Arts and learning in STEM subjects. Life is long. Most people will change careers several times. What do we gain by forcing students to choose such a rigid path so early? More importantly, how much do we loose? How inflexible does our workforce become when people have been steered so powerfully towards focusing on one narrow thing? How devastating for them when it doesn’t work out. I remember playing Trivial Pursuit with my grandfather, whose degree was in History but who was also a Geologist and prospector. He could answer any trivia question. He could also light a fire in the pouring rain, but that’s another post altogether. We need to foster that kind of flexible thinking and learning in our schools, not squash it by forcing students to make a stark choice.

Finally, the most troubling assumption that’s made about learning in the Arts is that the skills we teach aren’t valuable or marketable. People seem to have this image in their heads of a rail-thin starving artist in a cold garret, painting his un-sellable canvases and eating stale bread. That image is so far away from the reality of the artists I graduated with as to be laughable. Some of my former classmates are still pursuing performing careers but many have parlayed their expertise into careers in medicine, education, design, or management. The performers too are rarely doing just one thing; often they’re pursuing multiple career pathways at once… triumphantly. If you want to learn about successful career transitions, ask an artist.

All of the skills that we’ve now labeled “Global Competencies” (formerly known as 21C) are taught through the Arts.

Critical Thinking and Problem Solving? Ask a theatre company who has to tour a show with an ensemble cast, a modular set, and a shoestring budget.

Innovation, Creativity and Entrepreneurship? Ask an independent dance artist who has to write grant proposals, organize a summer dance camp for children, perform and stage her own work, and market herself to festivals.

Collaboration? Join an orchestra, a band, or the cast of a play… you’ll be an expert on collaboration.

Communication? In the Arts we practice communicating in every way possible: visually, acoustically, linguistically, through body language and movement, among others. When words fail, we step up.

Citizenship? Look at any progressive movement in history; you’ll find artists at the forefront, pushing for a fairer, more diverse, better world.

Self-directed Learning? That’s our bread and butter. Artists are constantly seeking out opportunities to learn from each other in order to move their practice forward. In the absence of an obvious pathway, we create our own.

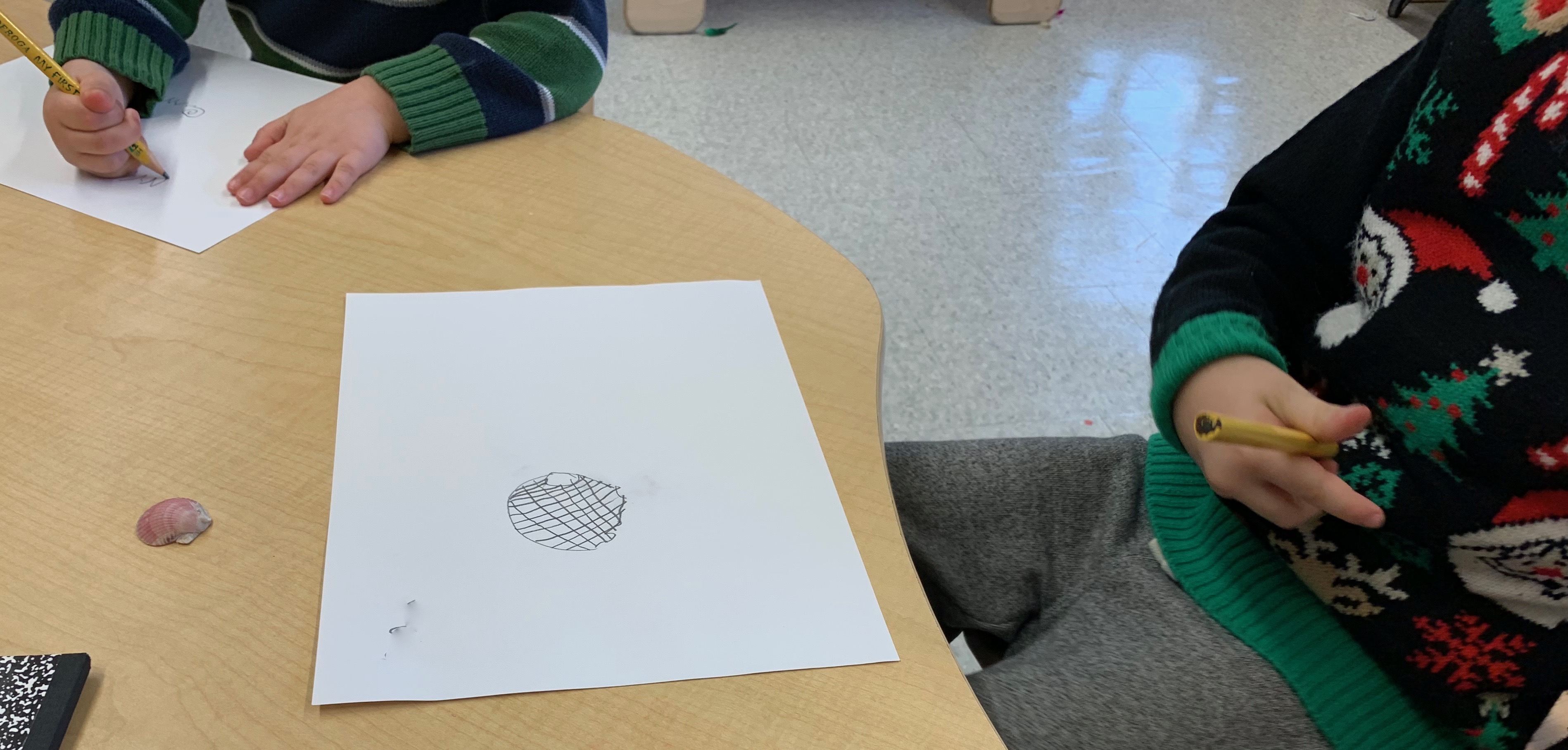

If you’re reading this post and sensing a certain desperation in my tone, you’re not wrong. I am feeling a little desperate. I’m frightened for our kids. I’m scared and sad for the kids who have enormous potential as artists-in-progress, and are put off pursuing their passions by well-intentioned but ill-informed adults. I’m also afraid for the many students who are struggling with anxiety and depression, whose pursuit of a perfect transcript has left them floundering with no way to express their angst. Put some clay in their hands, give them a brush, or a role, or a trumpet… let them create. Most importantly, don’t tell them that they have to choose. The things they’ll learn in arts classes, be they in high school or beyond, will serve them well for the rest of their lives, whether or not they go on to a career in the Arts as we have traditionally conceptualized it. They will learn exactly the skills they will need to navigate this uncertain world, a world of career changes, entrepreneurship, and acrobatic flexibility.

We are a culture in love with the dichotomy but we have to get over it… fast. The world is changing all around us and without these 21C/Global Competencies, we’re going to be left behind. It’s not either STEM or Arts, it’s AND.